In today's paper, for participants who received two standard doses, vaccine efficacy was 62.1%.

In participants who received a low dose followed by a standard dose, efficacy was 90.0%.

This was described as "intriguingly high compared with the other findings in the study. Although there is a possibility that chance might play a part in such divergent results."

Professor Andrew Pollard, director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, Department of Paediatrics, University of Oxford, told a news briefing hosted by the Science Media Centre that the half dose, full dose approach that gave the best results wasn't planned. He dismissed concerns about the age of participants in that group saying the result "doesn't appear to be an age phenomenon".

Overall vaccine efficacy across both groups was 70.4%.

Regulators and UK vaccination advisers would have to assess which regimen might be selected for approval, Prof Pollard said.

The vaccine was found to be safe, the authors said, with only three out of 23,745 participants over a median of 3.4 months experiencing serious adverse events that were possibly related to a vaccine; one in the vaccine arm, one in the control arm, and one in a participant who remains masked to group allocation. All participants have recovered or are recovering, and remain in the trial.

The paper said: "A case of transverse myelitis was reported 14 days after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 booster vaccination as being possibly related to vaccination, with the independent neurological committee considering the most likely diagnosis to be of an idiopathic, short segment, spinal cord demyelination."

Prof Pollard said: "I think today is an important landmark for us because the data package that is in this paper is being put forward to regulators to consider and to scrutinise so there's these two different aspects of scrutiny, there's the scientific peer review for publication, and also the regulatory processes which I'm sure we'll hear more about in the weeks ahead."

Professor Sarah Gilbert, Jenner Institute, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, said: "This is a really good day in the UK. This is probably the best day we've had in 2020. Not only today are we seeing the first rollout of NHS vaccinations against COVID-19, from our side we're able to present to you our data in a full peer reviewed publication."

In a linked comment, Dr Maria Deloria Knoll and Dr Chizoba Wonodi, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, USA, who were not involved in the study, said: "Despite the outstanding questions and challenges in delivering these vaccines, it is hard not to be excited about these findings and now the existence of three safe and efficacious COVID-19 vaccines, with 57 more in clinical trials."

Professor Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, commented: "These results reflect the headlines given in previous press releases, but with both a fuller explanation of what was done and more detail around the uncertainty in the estimates of efficacy.

"The unfortunate [half dose] measurement technique problem that occurred with some doses produced in Italy is going to be seen by some as raising questions about this trial. It is clear however, that national and international regulators were fully apprised of what had happened and a plan for analysis was determined prior to knowledge of the results."

Coronavirus vaccines have become a reality, as they are now being approved and authorized for use in a growing number of countries including the United States. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has just issued emergency authorization for the use of the COVID-19 vaccine produced by Pfizer and BioNTech. Close behind is the vaccine developed by Moderna, which has also applied to the FDA for emergency authorization.

The efficacy of a two-dose administration of the vaccine has been pegged at 95.0%, and the FDA has said that the 95% credible interval for the vaccine efficacy was 90.3%-97.6%. But as with many initial clinical trials, whether for drugs or vaccines, not all populations were represented in the trial cohort, including individuals who are immunocompromised. At the current time, it is largely unknown how safe or effective the vaccine may be in this large population, many of whom are at high risk for serious COVID-19 complications.

At a special session held during the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Anthony Fauci, MD, the nation's leading infectious disease expert, said that individuals with compromised immune systems, whether because of chemotherapy or a bone marrow transplant, should plan to be vaccinated when the opportunity arises.

In response to a question from ASH President Stephanie J. Lee, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, Fauci emphasized that, despite being excluded from clinical trials, this population should get vaccinated. "I think we should recommend that they get vaccinated," he said. "I mean, it is clear that, if you are on immunosuppressive agents, history tells us that you're not going to have as robust a response as if you had an intact immune system that was not being compromised. But some degree of immunity is better than no degree of immunity."

That does seem to be the consensus among experts who spoke in interviews: that as long as these are not live attenuated vaccines, they hold no specific risk to an immunocompromised patient, other than any factors specific to the individual that could be a contraindication.

"Patients, family members, friends, and work contacts should be encouraged to receive the vaccine," said William Stohl, MD, PhD, chief of the division of rheumatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. "Clinicians should advise patients to obtain the vaccine sooner rather than later."

Kevin C. Wang, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, agreed. "I am 100% with Fauci. Everyone should get the vaccine, even if it may not be as effective," he said. "I would treat it exactly like the flu vaccines that we recommend folks get every year."

Wang noted that he couldn't think of any contraindications unless the immunosuppressed patients have a history of severe allergic reactions to prior vaccinations. "But I would even say patients with history of cancer, upon recommendation of their oncologists, are likely to be suitable candidates for the vaccine," he added. "I would say clinicians should approach counseling the same way they counsel patients for the flu vaccine, and as far as I know, there are no concerns for systemic drugs commonly used in dermatology patients."

However, guidance has not yet been issued from either the FDA or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention regarding the use of the vaccine in immunocompromised individuals. Given the lack of data, the FDA has said that "it will be something that providers will need to consider on an individual basis," and that individuals should consult with physicians to weigh the potential benefits and potential risks.

The CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has said that clinicians need more guidance on whether to use the vaccine in pregnant or breastfeeding women, the immunocompromised, or those who have a history of allergies. The CDC itself has not yet released its formal guidance on vaccine use.

COVID-19 Vaccines

Vaccines typically require years of research and testing before reaching the clinic, but this year researchers embarked on a global effort to develop safe and effective coronavirus vaccines in record time. Both the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines have only a few months of phase 3 clinical trial data, so much remains unknown about them, including their duration of effect and any long-term safety signals. In addition to excluding immunocompromised individuals, the clinical trials did not include children or pregnant women, so data are lacking for several population subgroups.

But these will not be the only vaccines available, as the pipeline is already becoming crowded. U.S. clinical trial data from a vaccine jointly being developed by Oxford-AstraZeneca, could potentially be ready, along with a request for FDA emergency use authorization, by late January 2021.

In addition, China and Russia have released vaccines, and there are currently 61 vaccines being investigated in clinical trials and at least 85 preclinical products under active investigation.

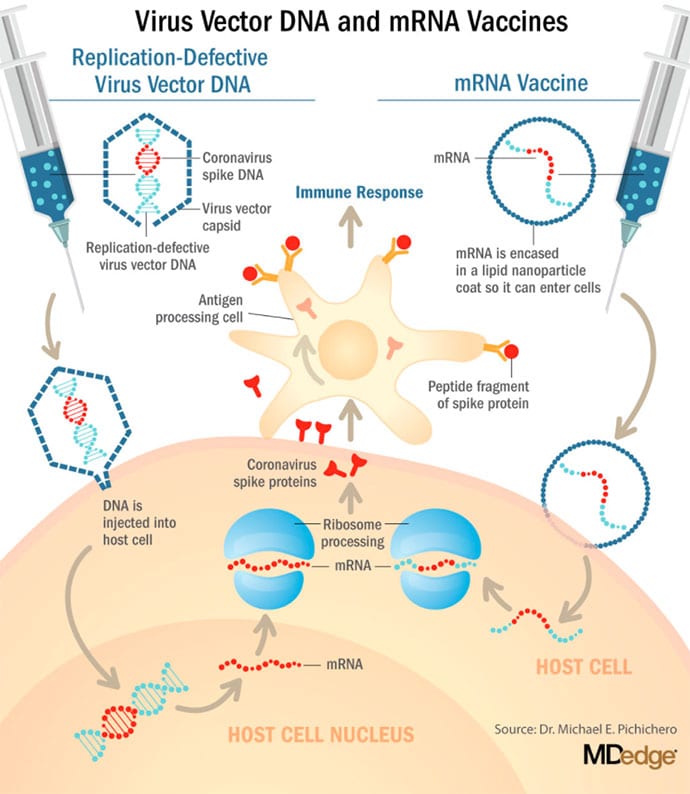

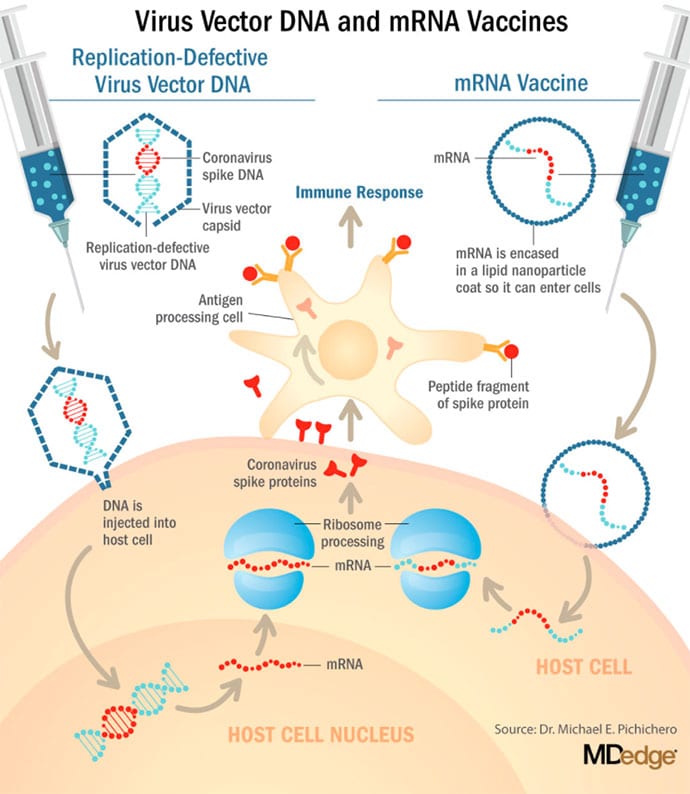

The vaccine candidates are using both conventional and novel mechanisms of action to elicit an immune response in patients. Conventional methods include attenuated inactivated (killed) virus and recombinant viral protein vaccines to develop immunity. Novel approaches include replication-deficient, adenovirus vector-based vaccines that contain the viral protein, and mRNA-based vaccines, such as the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, that encode for a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

"The special vaccine concern for immunocompromised individuals is introduction of a live virus," Stohl said. "Neither the Moderna nor Pfizer vaccines are live viruses, so there should be no special contraindication for such individuals."

Live vaccine should be avoided in immunocompromised patients, and currently, live SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are only being developed in India and Turkey.

It is not unusual for vaccine trials to begin with cohorts that exclude participants with various health conditions, including those who are immunocompromised. These groups are generally then evaluated in phase 4 trials, or postmarketing surveillance. While the precise number of immunosuppressed adults in the United States is not known, the numbers are believed to be rising because of increased life expectancy among immunosuppressed adults as a result of advances in treatment and new and wider indications for therapies that can affect the immune system.

According to data from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, an estimated 2.7% of U.S. adults are immunosuppressed. This population covers a broad array of health conditions and medical specialties; people living with inflammatory or autoimmune conditions, such as inflammatory rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, lupus); inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis); psoriasis; multiple sclerosis; organ transplant recipients; patients undergoing chemotherapy; and life-long immunosuppression attributable to HIV infection.

As the vaccines begin to roll out and become available, how should clinicians advise their patients, in the absence of any clinical trial data?

Risk vs. Benefit

Gilaad Kaplan, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at the University of Calgary (Alta.), noted that the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) community has dealt with tremendous anxiety during the pandemic because many are immunocompromised because of the medications they use to treat their disease.

"For example, many patients with IBD are on biologics like anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapies, which are also used in other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis," he said. "Understandably, individuals with IBD on immunosuppressive medications are concerned about the risk of severe complications due to COVID-19."

The entire IBD community, along with the world, celebrated the announcement that multiple vaccines are protective against SARS-CoV-2, he noted. "Vaccines offer the potential to reduce the spread of COVID-19, allowing society to revert back to normalcy," Kaplan said. "Moreover, for vulnerable populations, including those who are immunocompromised, vaccines offer the potential to directly protect them from the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19."

That said, even though the news of vaccines are extremely promising, some cautions must be raised regarding their use in immunocompromised populations, such as persons with IBD. "The current trials, to my knowledge, did not include immunocompromised individuals and thus, we can only extrapolate from what we know from other trials of different vaccines," he explained. "We know from prior vaccines studies that the immune response following vaccination is less robust in those who are immunocompromised as compared to a healthy control population."

Kaplan also pointed to recent reports of allergic reactions that have been reported in healthy individuals. "We don't know whether side effects, like allergic reactions, may be different in unstudied populations," he said. "Thus, the medical and scientific community should prioritize clinical studies of safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised populations."

So, what does this mean for an individual with an immune-mediated inflammatory disease like Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis who is immunocompromised? Kaplan explained that it is a balance between the potential harm of being infected with COVID-19 and the uncertainty of receiving a vaccine in an understudied population. For those who are highly susceptible to dying from COVID-19, such as an older adult with IBD, or someone who faces high exposure, such as a health care worker, the potential protection of the vaccine greatly outweighs the uncertainty.

"However, for individuals who are at otherwise lower risk – for example, young and able to work from home – then waiting a few extra months for postmarketing surveillance studies in immunocompromised populations may be a reasonable approach, as long as these individuals are taking great care to avoid infection," he said.

No Waiting Needed

Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, feels that the newly approved vaccine should be safe for most of his patients.

"Patients with psoriatic disease should get the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible based on eligibility as determined by the CDC and local public health officials," he said. "It is not a live vaccine, and therefore patients on biologics or other immune-modulating or immune-suppressing treatment can receive it."

However, the impact of psoriasis treatment on immune response to the mRNA-based vaccines is not known. Gelfand noted that, extrapolating from the vaccine literature, there is some evidence that methotrexate reduces response to the influenza vaccine. "However, the clinical significance of this finding is not clear," he said. "Since the mRNA vaccine needs to be taken twice, a few weeks apart, I do not recommend interrupting or delaying treatment for psoriatic disease while undergoing vaccination for COVID-19."

Given the reports of allergic reactions, he added that it is advisable for patients with a history of life-threatening allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis or who have been advised to carry an epinephrine autoinjector, to talk with their health care provider to determine if COVID-19 vaccination is medically appropriate.

The National Psoriasis Foundation has issued guidance on COVID-19, explained Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and social sciences & health policy at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., who is also a member of the committee that is working on those guidelines and keeping them up to date. "We are in the process of updating the guidelines with information on COVID vaccines," he said.

He agreed that there are no contraindications for psoriasis patients to receive the vaccine, regardless of whether they are on immunosuppressive treatment, even though definitive data are lacking. "Fortunately, there's a lot of good data coming out of Italy that patients with psoriasis on biologics do not appear to be at increased risk of getting COVID or of having worse outcomes from COVID," he said.

Patients are going to ask about the vaccines, and when counseling them, clinicians should discuss the available data, the residual uncertainty, and patients' concerns should be considered, Feldman explained. "There may be some concern that steroids and cyclosporine would reduce the effectiveness of vaccines, but there is no concern that any of the drugs would cause increased risk from nonlive vaccines."

He added that there is evidence that "patients on biologics who receive nonlive vaccines do develop antibody responses and are immunized."

Boosting Efficacy

Even prior to making their announcement, the American College of Rheumatology had said that they would endorse the vaccine for all patients, explained rheumatologist Brett Smith, DO, from Blount Memorial Physicians Group and East Tennessee Children's Hospital, Alcoa. "The vaccine is safe for all patients, but the problem may be that it's not as effective," he said. "But we don't know that because it hasn't been tested."

With other vaccines, biologic medicines are held for 2 weeks before and afterwards, to get the best response. "But some patients don't want to stop the medication," Smith said. "They are afraid that their symptoms will return."

As for counseling patients as to whether they should receive this vaccine, he explained that he typically doesn't try to sway patients one way or another until they are really high risk. "When I counsel, it really depends on the individual situation. And for this vaccine, we have to be open to the fact that many people have already made up their mind."

There are a lot of questions regarding the vaccine. One is the short time frame of development. "Vaccines typically take 6-10 years to come on the market, and this one is now available after a 3-month study," Smith said. "Some have already decided that it's too new for them."

The process is also new, and patients need to understand that it doesn't contain an active virus and "you can't catch coronavirus from it."

Smith also explained that, because the vaccine may be less effective in a person using biologic therapies, there is currently no information available on repeat vaccination. "These are all unanswered questions," he said. "If the antibodies wane in a short time, can we be revaccinated and in what time frame? We just don't know that yet."

Philip D. Bonomi, MD, a professor of medical oncology at Rush Medical College, Chicago, explained that one way to ensure a more optimal response to the vaccine would be to wait until the patient has finished chemotherapy. "The vaccine can be offered at that time, and in the meantime, they can take other steps to avoid infection," he said. "If they are very immunosuppressed, it isn't worth trying to give the vaccine."

Cancer patients should be encouraged to stay as healthy as possible, and to wear masks and social distance. "It's a comprehensive approach. Eat healthy, avoid alcohol and tobacco, and exercise. [These things] will help boost the immune system," Bonomi said. "Family members should be encouraged to get vaccinated, which will help them avoid infection and exposing the patient."

Jim Boonyaratanakornkit, MD, PhD, an infectious disease specialist who cares for cancer patients at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, agreed. "Giving a vaccine right after a transplant is a futile endeavor," he said. "We need to wait 6 months to have an immune response."

He pointed out there may be a continuing higher number of cases, with high levels peaking in Washington in February and March. "Close friends and family should be vaccinated if possible," he said, "which will help interrupt transmission."

The vaccines are using new platforms that are totally different, and there is no clear data as to how long the antibodies will persist. "We know that they last for at least 4 months," said Boonyaratanakornkit. "We don't know what level of antibody will protect them from COVID-19 infection. Current studies are being conducted, but we don't have that information for anyone yet.

In mid-November, Pfizer/BioNTech were the first with surprising positive protection interim data for their coronavirus vaccine, BNT162b2. A week later, Moderna released interim efficacy results showing its coronavirus vaccine, mRNA-1273, also protected patients from developing SARS-CoV-2 infections. Both studies included mostly healthy adults. A diverse ethnic and racial vaccinated population was included. A reasonable number of persons aged over 65 years, and persons with stable compromising medical conditions were included. Adolescents aged 16 years and over were included. Younger adolescents have been vaccinated or such studies are in the planning or early implementation stage as 2020 came to a close.

These are new and revolutionary vaccines, although the ability to inject mRNA into animals dates back to 1990, technological advances today make it a reality.1 Traditional vaccines typically involve injection with antigens such as purified proteins or polysaccharides or inactivated/attenuated viruses. mRNA vaccines work differently. They do not contain antigens. Instead, they contain a blueprint for the antigen in the form of genetic material, mRNA. In the case of Pfizer's and Moderna's vaccines, the mRNA provides the genetic information to synthesize the spike protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and infect human cells. Each type of vaccine is packaged in proprietary lipid nanoparticles to protect the mRNA from rapid degradation, and the nanoparticles serve as an adjuvant to attract immune cells to the site of injection. (The properties of the respective lipid nanoparticle packaging may be the factor that impacts storage requirements discussed below.) When injected into muscle (myocyte), the lipid nanoparticles containing the mRNA inside are taken into muscle cells, where the cytoplasmic ribosomes detect and decode the mRNA resulting in the production of the spike protein antigen. It should be noted that the mRNA does not enter the nucleus, where the genetic information (DNA) of a cell is located, and can't be reproduced or integrated into the DNA. The antigen is exported to the myocyte cell surface where the immune system's antigen presenting cells detect the protein, ingest it, and take it to regional lymph nodes where interactions with T cells and B cells results in antibodies, T cell–mediated immunity, and generation of immune memory T cells and B cells. A particular subset of T cells – cytotoxic or killer T cells – destroy cells that have been infected by a pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine from Pfizer was reported to induce powerful cytotoxic T-cell responses. Results for Moderna's vaccine had not been reported at the time this column was prepared, but I anticipate the same positive results.

The revolutionary aspect of mRNA vaccines is the speed at which they can be designed and produced. This is why they lead the pack among the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates and why the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided financial, technical, and/or clinical support. Indeed, once the amino acid sequence of a protein can be determined (a relatively easy task these days) it's straightforward to synthesize mRNA in the lab – and it can be done incredibly fast. It is reported that the mRNA code for the vaccine by Moderna was made in 2 days and production development was completed in about 2 months.2

A 2007 World Health Organization report noted that infectious diseases are emerging at "the historically unprecedented rate of one per year."3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Zika, Ebola, and avian and swine flu are recent examples. For most vaccines against emerging diseases, the challenge is about speed: developing and manufacturing a vaccine and getting it to persons who need it as quickly as possible. The current seasonal flu vaccine takes about 6 months to develop; it takes years for most of the traditional vaccines. That's why once the infrastructure is in place, mRNA vaccines may prove to offer a big advantage as vaccines against emerging pathogens.

Early Efficacy Results Have Been Surprising

Both vaccines were reported to produce about 95% efficacy in the final analysis. That was unexpectedly high because most vaccines for respiratory illness achieve efficacy of 60%-80%, e.g., flu vaccines. However, the efficacy rate may drop as time goes by because stimulation of short-term immunity would be in the earliest reported results.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 cases is an important aspect of a coronavirus vaccine, but preventing severe illness is especially important considering that severe cases can result in prolonged intubation/artificial ventilation, prolonged disability and death. Pfizer/BioNTech had not released any data on the breakdown of severe cases as this column was finalized. In Moderna's clinical trial, a secondary endpoint analyzed severe cases of COVID-19 and included 30 severe cases (as defined in the study protocol) in this analysis. All 30 cases occurred in the placebo group and none in the mRNA-1273–vaccinated group. In the Pfizer/BioNTech trial there were too few cases of severe illness to calculate efficacy.

Duration of immunity and need to revaccinate after initial primary vaccination are unknowns. Study of induction of B- and T-cell memory and levels of long-term protection have not been reported thus far.

Could mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines Be Dangerous in the Long Term?

These will be the first-ever mRNA vaccines brought to market for humans. In order to receive Food and Drug Administration approval, the companies had to prove there were no immediate or short-term negative adverse effects from the vaccines. The companies reported that their independent data-monitoring committees hadn't "reported any serious safety concerns." However, fairly significant local reactions at the site of injection, fever, malaise, and fatigue occur with modest frequency following vaccinations with these products, reportedly in 10%-15% of vaccinees. Overall, the immediate reaction profile appears to be more severe than what occurs following seasonal influenza vaccination. When mass inoculations with these completely new and revolutionary vaccines begins, we will know virtually nothing about their long-term side effects. The possibility of systemic inflammatory responses that could lead to autoimmune conditions, persistence of the induced immunogen expression, development of autoreactive antibodies, and toxic effects of delivery components have been raised as theoretical concerns.4-6 None of these theoretical risks have been observed to date and postmarketing phase 4 safety monitoring studies are in place from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the companies that produce the vaccines. This is a risk public health authorities are willing to take because the risk to benefit calculation strongly favors taking theoretical risks, compared with clear benefits in preventing severe illnesses and death.

What About Availability?

Pfizer/BioNTech expects to be able to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Moderna expects to produce 20 million doses by the end of 2020, and 500 million to 1 billion doses in 2021. Storage requirements are inherent to the composition of the vaccines with their differing lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Pfizer/BioNTech's BNT162b2 has to be stored and transported at –80° C, which requires specialized freezers, which most doctors' offices and pharmacies are unlikely to have on site, or dry ice containers. Once the vaccine is thawed, it can only remain in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Moderna's mRNA-1273 will be much easier to distribute. The vaccine is stable in a standard freezer at –20° C for up to 6 months, in a refrigerator for up to 30 days within that 6-month shelf life, and at room temperature for up to 12 hours.

Timelines and Testing Other Vaccines

Strong efficacy data from the two leading SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and emergency-use authorization Food and Drug Administration approval suggest the window for testing additional vaccine candidates in the United States could soon start to close. Of the more than 200 vaccines in development for SARS-CoV-2, at least 7 have a chance of gathering pivotal data before the front-runners become broadly available.

Testing diverse vaccine candidates, based on different technologies, is important for ensuring sufficient supply and could lead to products with tolerability and safety profiles that make them better suited, or more attractive, to subsets of the population. Different vaccine antigens and technologies also may yield different durations of protection, a question that will not be answered until long after the first products are on the market.

AstraZeneca enrolled about 23,000 subjects into its two phase 3 trials of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19): a 40,000-subject U.S. trial and a 10,000-subject study in Brazil. AstraZeneca's AZD1222, developed with the University of Oxford (England), uses a replication defective simian adenovirus vector called ChAdOx1.AZD1222 which encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. After injection, the viral vector delivers recombinant DNA that is decoded to mRNA, followed by mRNA decoding to become a protein. A serendipitous manufacturing error for the first 3,000 doses resulted in a half dose for those subjects before the error was discovered. Full doses were given to those subjects on second injections and those subjects showed 90% efficacy. Subjects who received 2 full doses showed 62% efficacy. A vaccine cannot be licensed based on 3,000 subjects so AstraZeneca has started a new phase 3 trial involving many more subjects to receive the combination lower dose followed by the full dose.

Johnson and Johnson (J&J) started its phase 3 trial evaluating a single dose of JNJ-78436735 in September. Phase 3 data may be reported by the end of2020. In November, J&J announced it was starting a second phase 3 trial to test two doses of the candidate. J&J's JNJ-78436735 encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in an adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector, which is one of the two adenovirus vectors used in Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine reported to have 90% efficacy at an early interim analysis.

Sanofi and Novavax are both developing protein-based vaccines, a proven modality. Sanofi, in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline started a phase 1/2 clinical trial in the Fall 2020 with plans to commence a phase 3 trial in late December. Sanofi developed the protein ingredients and GlaxoSmithKline added one of their novel adjuvants. Novavax expects data from a U.K. phase 3 trial of NVX-CoV2373 in early 2021 and began a U.S. phase 3 study in late November. NVX-CoV2373 was created using Novavax' recombinant nanoparticle technology to generate antigen derived from the coronavirus spike protein and contains Novavax's patented saponin-based Matrix-M adjuvant.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals was gearing up to start a U.S. phase 2/3 trial of DNA vaccine INO-4800 by the end of 2020.

After Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, CureVac has the next most advanced mRNA vaccine. It was planned that a phase 2b/3 trial of CVnCoV would be conducted in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Sanofi is also developing a mRNA vaccine as a second product in addition to its protein vaccine.

Vaxxinity planned to begin phase 3 testing of UB-612, a multitope peptide–based vaccine, in Brazil by the end of 2020.

However, emergency-use authorizations for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines could hinder trial recruitment in at least two ways. Given the gravity of the pandemic, some stakeholders believe it would be ethical to unblind ongoing trials to give subjects the opportunity to switch to a vaccine proven to be effective. Even if unblinding doesn't occur, as the two authorized vaccines start to become widely available, volunteering for clinical trials may become less attractive.

Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Pichichero at pdnews@mdedge.com.

.

Earlier this week, Medscape spoke with Nora Disis, MD, about vaccinating cancer patients. Disis is a medical oncologist and director of both the Institute of Translational Health Sciences and the Cancer Vaccine Institute, the University of Washington, Seattle, Washington. As editor-in-chief of JAMA Oncology, she has watched COVID-19 developments in the oncology community over the past year.

Here are a few themes that Disis said oncologists should be aware of as vaccines eventually begin reaching cancer patients.

We should expect cancer patients to respond to vaccines. Historically, some believed that cancer patients would be unable to mount an immune response to vaccines. Data on other viral vaccines have shown otherwise. For example, there has been a long history of studies of flu vaccination in cancer patients, and in general, those vaccines confer protection. Likewise for pneumococcal vaccine, which, generally speaking, cancer patients should receive.

Special cases may include hematologic malignancies in which the immune system has been destroyed and profound immunosuppression occurs. Data on immunization during this immunosuppressed period are scarce, but what data are available suggest that once cancer patients are through this immunosuppressed period, they can be vaccinated successfully.

The type of vaccine will probably be important for cancer patients. Currently, there are 61 coronavirus vaccines in human clinical trials, and 17 have reached the final stages of testing. At least 85 preclinical vaccines are under active investigation in animals.

Both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines are mRNA type. There are many other types, including protein-based vaccines, viral vector vaccines based on adenoviruses, and inactivated or attenuated coronavirus vaccines.

The latter vaccines, particularly attenuated live virus vaccines, may not be a good choice for cancer patients. Especially in those with rapidly progressing disease or on chemotherapy, attenuated live viruses may cause a low-grade infection.

Incidentally, the technology used in the genetic, or mRNA, vaccines developed by both Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna was initially developed for fighting cancer, and studies have shown that patients can generate immune responses to cancer-associated proteins with this type of vaccine.

These genetic vaccines could turn out to be the most effective for cancer patients, especially those with solid tumors.

Our understanding is very limited right now. Neither the Pfizer-BioNTech nor the Moderna early data discuss cancer patients. Two of the most important questions for cancer patients are dosing and booster scheduling. Potential defects in lymphocyte function among cancer patients may require unique initial dosing and booster schedules. In terms of timing, it is unclear how active therapy might affect a patient's immune response to vaccination and whether vaccines should be timed with therapy cycles.

Vaccine access may depend on whether cancer patients are viewed as a vulnerable population. Those at higher risk for severe COVID-19 clearly have a greater need for vaccination. While there are data suggesting that cancer patients are at higher risk, they are a bit murky, in part because cancer patients are a heterogeneous group. For example, there are data suggesting that lung and blood cancer patients fare worse. There is also a suggestion that, like in the general population, COVID risk in cancer patients remains driven by comorbidities.

It is likely, then, that personalized risk factors such as type of cancer therapy, site of disease, and comorbidities will shape individual choices about vaccination among cancer patients.

Scientists are now confident that a new variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is more contagious but say studies are underway to test its impact on containing COVID-19

What is different about this variant?

The new variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, known as VUI-202012/01, or lineage B.1.1.7, carries an unusually large number of mutations.

Three of the mutations have potential biological effects. These have been identified as:

Mutation N501Y – one of six key contact residues within the receptor-binding domain that can increase binding affinity to human and murine ACE2.

The spike deletion 69-70del that affects the capacity to evade human immune response

Mutation P681H adjacent to the furin cleavage site

How was it identified?

The variant was identified by Public Health England monitoring, following a surge in cases seen in Kent and London.

The two earliest sampled genomes belonging to B.1.1.7 lineage were collected on 20 September in Kent, followed by another on 21 September in Greater London.

How widespread is it?

According to the COVID-19 Genomics Consortium UK (COG-UK), as of 15 December, there were 1623 genomes in the B.1.1.7 lineage.

Of these 519 were sampled in Greater London, 555 in Kent, 545 in other regions of the UK including both Scotland and Wales, and four in other countries.

Is it more contagious?

Genomic data suggests a growth rate of the new virus variant 71% higher (95% confidence level: 67% - 75%) than other variants.

Although it remains too early to say with certainty that the variant is responsible for increased numbers of cases, the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG) said on 18 December that the variant had "demonstrated exponential growth during a period when national lockdown measures were in place".

The panel concluded that that VUI-202012/01 "demonstrates a substantial increase in transmissibility compared to other variants".

Is the new variant more dangerous?

Sharon Peacock, executive director of COG-UK, told a briefing hosted by the Science Media Centre yesterday: "We have no evidence that there is an association with a worse outcome."

Prof Tom Connor, reader at the School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, said it was too early to be sure, as outcomes were determined after 28 days following diagnosis. "We're not at that point where you'd have that outcome information to do that analysis yet," he told the briefing.

Public Health England has said: "We currently have no evidence that the variant is more likely to cause severe disease or mortality – but we are continuing investigations to understand this better."

Is the UK alone in being identified with the variant?

Experts have suggested that UK science might be just better at identifying variant strains of the virus than most other countries.

According to Prof Connor, "It is probable that similar variants are popping up around the world.

"We are sequencing in the UK at a disproportionate rate to other people, which means that we have a much better system for catching this," he told the briefing.

Is there any evidence that children are spreaders now?

At a news conference this week, Boris Johnson evaded a commitment that all children would be back at school at the start of January, reflecting suggestions that school-age children might be spreading the virus.

Experts today said that there was no evidence this was the case.

However, Judith Breuer, professor of virology and co-director of the Division of Infection and Immunity at University College London said: "We know that coronavirus is spread very easily amongst children, so it wouldn't surprise me if eventually the SARS-CoV-2 virus ended up spreading amongst children."

Will the new variant be resistant to current vaccines?

There is no current evidence that the new variant of SARS-CoV-2 will be resistant to COVID-19 vaccines.

PHE said this week that laboratory work was currently being undertaken as a priority to understand this.

Professor Ravi Gupta, professor of clinical microbiology at the University of Cambridge said that "the new variant is very unlikely to escape vaccines because vaccines elicit T-cell responses, antibody responses, and both of those responses are targeting multiple parts of the spike".

Ugur Sahin from BioNTech, whose COVID-19 vaccine was the first to be approved for emergency use worldwide, and in the UK, said he was confident the company's vaccine would remain effective against the new variant.

However, he acknowledged that more research was needed before he could confirm the efficacy.

Was this new variant unexpected?

It is not uncommon for viruses to undergo mutations; seasonal influenza mutates every year. Variants of SARS-CoV-2 have been observed in other countries, such as Spain.

Prof Tom Solomon, director of the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, at the University of Liverpool, said: "SARS-CoV-2, the virus which causes COVID-19, is evolving and mutating all the time, as do all similar viruses. Such changes are completely to be expected."

Dr Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, said the latest development showed there would still be surprises from SARS-CoV-2. "We have to remain humble and be prepared to adapt and respond to new and continued challenges as we move into 2021," he said.